Table of Contents

Top of page

Name

Summary

Distribution Map

Property List

Profile

Bibliography

Bottom of page

Alsige 9

Alsige of Faringdon (Berkshire), fl. 1066x1086

Male

SDB

4 of 5

Summary

Alsige of Faringdon was one of the few landholders in 1066 who not only survived the conquest but also prospered during the Conqueror’s reign, and his career has attracted some attention for that reason (Round 1906: 292−3; Stenton 1939: 388; Williams 1991: 118−9; Blair 1994: 175−8). It is suggested here that his success was a function of his talent for estate management, a skill much prized by the Normans who needed able administrators to maximise the income generated from their newly-acquired lands. Alsige appears to have shared this talent with his son, Alwig, who probably served the king as a sheriff at some stage during his career. Both men increased the profitability of their own estates significantly between 1066 and 1086, and it is possible to suggest how they did so: by extracting heavy rents from the peasantry, and by making effective use of the various resources at their disposal – connections with towns, control of water transport, and trade in wool, salt, fish and stone. It is also possible to suggest how Alsige spent some of his money: certainly on a fine stone-built church, one of most complete and atmospheric examples of Anglo-Norman ‘overlap’ architecture, and possibly on one of England’s earliest rural stone-built keeps.Distribution map of property and lordships associated with this name in DB

List of property and lordships associated with this name in DB

Holder 1066

| Shire | Phil. ref. | Vill | DB Spelling | Holder 1066 | Lord 1066 | Tenant-in-Chief 1086 | 1086 Subtenant | Fiscal Value | 1066 Value | 1086 Value | Conf. | Show on Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berkshire | 1,40 | Littleworth | Alsi | Alsige of Faringdon | Harold, earl | William, king | Alsige of Faringdon | 2.00 | 1.94 | 1.65 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 78,12 | Longley | Elsi | Alsige of Faringdon | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | - | Map |

| Totals | ||||||||||||

Tenant-in-Chief 1086 demesne estates (no subtenants)

| Shire | Phil. ref. | Vill | DB Spelling | Holder 1066 | Lord 1066 | Tenant-in-Chief 1086 | 1086 Subtenant | Fiscal Value | 1066 Value | 1086 Value | Conf. | Show on Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berkshire | 65,7 | Barcote | Alsi | Harold, earl | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 5.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | - | Map |

| Berkshire | 65,8 | Wantage | Alsi | Ælfric 'of Wantage' | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 78,1 | Windrush | Elsi | Leofwine 'of Windrush' | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 1.16 | 1.00 | 2.70 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 78,1 | Windrush | Elsi | Wulfric 'of Windrush' | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 1.16 | 1.00 | 2.70 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 78,1 | Windrush | Elsi | Tovi Wendish | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 1.16 | 1.00 | 2.70 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 78,12 | Longley | Elsi | Alsige of Faringdon | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | - | Map |

| Oxfordshire | 58,28 | Radcot | Alsi | - | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 2.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | - | Map |

| Oxfordshire | 58,29 | Shipton-under-Wychwood | Alsi | Harold, earl | - | Alsige of Faringdon | - | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | - | Map |

| Totals | ||||||||||||

Subtenant in 1086

| Shire | Phil. ref. | Vill | DB Spelling | Holder 1066 | Lord 1066 | Tenant-in-Chief 1086 | 1086 Subtenant | Fiscal Value | 1066 Value | 1086 Value | Conf. | Show on Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berkshire | 1,34 | Great Faringdon | Alsi | - | - | William, king | Alsige of Faringdon | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.50 | - | Map |

| Berkshire | 1,40 | Littleworth | Alsi | Alsige of Faringdon | Harold, earl | William, king | Alsige of Faringdon | 2.00 | 1.94 | 1.65 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 11,14 | Windrush | Elsi | Bolla 'of Windrush' | - | Ralph, abbot of Winchcombe | Alsige of Faringdon | 3.50 | 8.00 | 8.00 | - | Map |

| Gloucestershire | 1,66 | Great Barrington | Elsi | Tovi Wendish | Harold, earl | William, king | Alsige of Faringdon | 4.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | - | Map |

| Oxfordshire | 1,8 | Langford | Alsi | Harold, earl | - | William, king | Alsige of Faringdon | 15.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 | - | Map |

| Oxfordshire | 1,9 | Shipton-under-Wychwood | Alsi | Harold, earl | - | William, king | Alsige of Faringdon | 8.00 | 10.00 | 9.00 | - | Map |

| Totals | ||||||||||||

Profile

Identification

Domesday Book refers to this person as Alsi de ferendone and as Elsi de ferendone, and two problems stem from this. First, although we are fortunate that Domesday Book supplies a toponymic byname – indeed, this is the foundation on which his identification rests − we cannot be certain that our man is only named in those entries where his byname occurs, for Domesday Book tends to omit the bynames of subtenants. Second, it is not clear what Old English name Alsi and Elsi were meant to represent. The Domesday scribes consistently used the ‘-si’ element to represent Old English names ending in ‘-sige’, but they also used ‘Al-’ or ‘El-’ to represent names beginning with ‘Ælf-’, ‘Æþel-’, ‘Eald-’ and ‘Ealh-’ as well as ‘Al-’ (Von Feilitzen 1937: 45−7, 69, 116−7, 142, 151−2, 187−8). It is therefore theoretically possible that Alsi and Elsi could refer to a man named Ælfsige, Æthelsige, Alsige, Ealdsige, or Ealhsige. However, the usual convention is adopt the simplest name form, unless Domesday Book or another text supplies clear evidence that a particular form was intended, and Alsige is therefore used here.

Five entries in Domesday Book use the toponymic ‘of Faringdon’ or claimed to hold, three estates directly from King William as a minor tenant-in-chief in 1086.

(i) Barcote in Berkshire. Alsi de Ferendone held 2 hides valued at £5 in 1086 ‘by gift of King William’, which had been held by Earl Harold TRE. This entry occurs in a group of holdings listed under the title ‘the land of Odo and other thegns’ at the end of the Berkshire Domesday; the vill had been assessed at 5 hides in 1066 (GDB 63c (Berkshire 65:7)).

(ii) ‘In Wantage hundred’. The entry after that for Barcote records that the same Alsi held half a hide valued at 10 shillings in 1086 at an unnamed location in Wantage hundred, which had been held by a certain free man named Ælfric TRE (GDB 63c (Berkshire 65:8)).

(iii) Windrush in Gloucestershire. Elsi de ferendone held 3.5 hides valued at £8 in 1086 ‘from the king’, which had been held ‘as three manors’ by men named Wulfric, Tovi and Leofwine TRE. This entry is the first listed under the heading ‘land of the king’s thegns’ at the end of the Gloucestershire Domesday (GDB 170c (Gloucestershire 78:1)). Alsige’s tenure of this estate was apparently disputed at the time of the survey, for another in the Gloucestershire Domesday records that Elsi de ferendone held 3.5 hides valued at £8 at Windrush from the abbot of Winchcombe in 1086. This goes on to assert that a certain ‘Bolla held it and gave it to the abbey’; that the estate was formerly held by men named Wulfric, Tovi and Leofwine, who held 2 hides, 5 virgates and 1 virgate there respectively; and that Alsige held it injuste ‘unjustly’ (GDB 165d (Gloucestershire 11:14)). This entry is not straight-forward to interpret, but one possible reconstruction is that Bolla was the father of Wulfric, Tovi and Leofwine; that he granted them a life interest in shares of the estate at Windrush, with reversion to the church of Winchcombe when they died; that these men were dispossessed at some stage after 1066; and that Alsige subsequently acquired the estate, leading to a dispute between him and the abbot of Winchcombe, who still claimed it by virtue of Bolla’s grant in 1086.

In addition, Alsige ‘of Faringdon’ is said to have held two estates from King William ‘at farm’ in 1086 (the significance of this formula is explored below).

(iv) Langford and Shipton-under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire. King William held estates assessed at 15 and 8 hides and valued at £18 and £9 respectively in 1086. Both of these estates were held by Earl Harold TRE and by Alsi de ferend(one) ad firmam in 1086 (GDB 154d (Oxfordshire 1:8−9)).

(v) Great Barrington in Gloucestershire. King William held 4 hides valued at £7 in 1086, which had been held by Tovi Wendish (Tovi 18), a housecarl of Earl Harold TRE. The text asserts that Elsi de ferendone held this in firma regis in 1086 (GDB 164b (Gloucestershire 1:66)).

There are also grounds for attributing a further five estates to the same Alsige, even though the relevant Domesday entries in question do not use his toponymic.

(i) Great Faringdon in Berkshire. Domesday Book records that King William held 30 hides valued at £21 6s 8d in 1086, which had been held by Earl Harold in 1066; and that Alsi held 4 hides of this manor valued at 30 shillings in 1086 (GDB 57d (Berkshire 1:34)). The place-name confirms that this was Alsige of Faringdon: the omissions of the toponymic in this case is readily explicable, for as we have seen, the Great Domesday scribe routinely omitted the bynames of subtenants.

(ii) Littleworth in Berkshire. Domesday Book records that Alsi held 2 hides in both 1066 and 1086; this formed part of a manor assessed at 31 hides which was held by Earl Harold TRE and by King William in 1086 (GDB 58a (Berkshire 1:40)). There are good reasons for identifying this Alsi as Alsige of Faringdon. First, Littleworth lay close to Alsige’s estate at Barcote; indeed, Barcote later became absorbed within the township of Littleworth. Second, several of Alsige of Faringdon’s known estates were, like Littleworth, held by Earl Harold TRE and by King William in 1086. Third, Alsige’s holding at Littleworth closely resembles Alsige of Faringdon’s holdings at Shipton-under-Wychwood and Great Faringdon, in that all three comprised small parcels of property carved out of larger royal manors.

(iii) Shipton-under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire. Domesday Book records that Alsi held 2 hides valued at 40 shillings in 1086, which had been held by Earl Harold TRE. As we have seen, a separate entry records that Alisge ‘of Faringdon’ held Shipton-under-Wychwood at farm in 1086 (GDB 160v (Oxfordshire 58:29); cf. GDB 154v (Oxfordshire 1:9).

(iv) Rocote in Oxfordshire. Domesday Book records that the same Alsi held from the king 2 hides valued at £4 there in 1086; the pre-Conquest landholder of this estate is not identified (GDB 160d (Oxfordshire 58:28)). He can be identified as Alsige of Faringdon, for the entry in question precedes that for Shipton-under-Wychwood, and follows an entry which records his son’s possession of Bletchingdon (see below). Rocote has sometimes been identified with Rycote near Thame (rendered Reicote elsewhere in Domesday Book), but Radcot is overwhelmingly more likely. Radcot is spelt Ratcota in a text of c. 1150 and Rotcote in 1220. Its location fits better with Alsige of Faringdon’s known estates, for whereas Radcot lies at their centre, Rycote would be an outlier in south-east Oxfordshire. In addition, a survey of 1279 records that a tenement in Windrush was attached to Radcot at that date; and as we have seen, Alsige of Faringdon held land at Windrush in 1086 (Stone and Hyde 1968: 57).

(v) Longney-on-the-Severn in Gloucestershire. Domesday Book records that a certain Elsi held 5 hides there in 1066 and 1086 (GDB 170c (Gloucestershire 78:12)). The grounds for identifying him with Alsige of Faringdon are firstly that the latter is explicitly named as the holder of Windrush eleven entries earlier on the same folio (GDB 170c (Gloucestershire 78:1)); and secondly that the Domesday-related text known as ‘Evesham K’ (London, British Library Cotton Vespasian B xxiv, fos. 57r−62r) lists the entries for Windrush and Longney consecutively, strongly suggesting they were held by the same Elsi. The relevant text occurs on fol. 62 r: ‘In Wenrich iii hidae et dimidia. In Langenie v hidae’, with ‘Elsi in Bernintone hundredo’ and ‘Elsi In Witestan hundredo’ written interlineally above. (The text is edited and discussed by Clarke 1977: 246–70, 553–68; see also Moore 1982, unpaginated appendix and note to entry 78:12, where Alsige of Longney is identified with Alsige of Faringdon on the evidence of ‘Evesham K’.)

The identification of Alsige of Faringdon with the tenant of Longney is attractive, since the latter is the subject of an engaging story transmitted in William of Malmesbury’s Vita Wulfstani. This describes how Alsige enjoyed leisure beneath a nut tree next to his proprietary church, until Saint Wulfstan (bishop of Worcester, 1062–1095) spoiled the party:

One Alsige (Eielsius), who had been a thegn of King Edward, invited Wulfstan to his vill of Longney on the Severn to dedicate a church. He never made difficulties about something like that, but when he arrived he found that there was not enough room for the people who had, as usual, come in droves to hear him. What is more, there was in the churchyard a nut tree which provided shade with its spreading leaves, but whose luxuriant branches denied light to the church. The bishop summoned his host and gave orders for the felling of the tree: it was only proper that, if nature had not provided enough room, he should supplement it by his own efforts, and certainly not take over for his own low pursuits space that nature had given − for the man had the habit of spending leisure time under the tree, especially on a summer’s day, dicing or feasting, or indulging in some other kind of jollification. That was why the man, far from obeying humbly, obstinately refused, and fell, as he later admitted, into such impudent madness that he was prepared to see the church undedicated rather than have the tree cut down. The saint, in no small degree provoked by this impertinence, hurled the spear of his curse at the tree. From the wound it gradually grew barren, failed in its fruit, and shrivelled up from the root. This sterility so irked the owner that in is annoyance he ordered the felling of a tree he had jealously owned but dearly longed to keep. The bishop told the story later to Coleman, when he returned to the vill, and showed him the spot in proof of the miracle. And Coleman always maintained and expressed the firm view that nothing could be more bitter than the curse of Wulfstan, or more agreeable than his blessing (Winterbottom and Thompson 2002: 94−7).

Eleventh-century thegns are known to have built residences and churches in close proximity; indeed, this combination was considered important among the elements which defined thegnly status (William 1992; Williams 2008: 85−104). It is therefore probable that the manor farm at Longney, which still stands to south of the churchyard, marks the place where Alsige’s hall stood in the late eleventh century; the nut tree perhaps stood on the spot now marked by a small mound on the south side of the church.

It is possible that Alsige of Faringdon made one further impression on the narrative sources for the conquest period, for the History of the Church of Abingdon (completed in the early 1160s, drawing on earlier material) devotes a chapter to a royal reeve named Alfsi. This Alfsi is said to have been the reeve responsible for the royal manor at Sutton Courtenay, neighbouring Abingdon itself, and is accused of ‘frequently and barbarously’ infringing upon the abbey’s ancient rights, in particular by exacting carrying services. This drew a sharp response from Abbot Adelelm, who on two occasions punished his audacity: once by striking him with his staff, and on another occasion by forcing Alfsi to abandon his carts and escape on foot, wading up to his neck in water across the river Ock. Alfsi subsequently complained about his mistreatment and, because the king was then in Normandy, the case was heard by Queen Matilda at Windsor: the liberties of the church were there endorsed, but Adelelm had to pay compensation to the king’s official (Hudson 2002–7: ii, 14–16). It is impossible to be certain that the reeve in question was Alsige of Faringdon, but since the latter is known to have managed royal estates on either side of the Thames Valley at this date, he is by far the most likely candidate.

Alwig son of Alsige of Faringdon

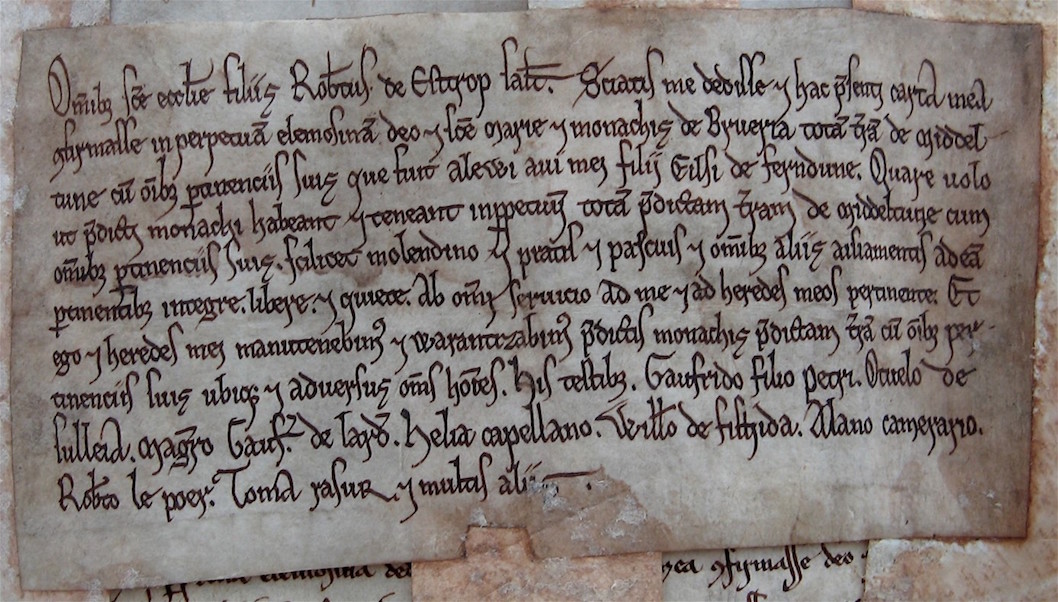

The account of Wallingford in the Berkshire Domesday records that filius Alsi de Ferendone held a house-plot (haga) there ‘which he says the king gave him’ (GDB 56b (Berkshire B:1)). The son is not named in this entry, but an early-thirteenth-century charter records that a certain Robert of Astrop granted land at Milton-under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire to Bruern Abbey, which was held by Robert’s grandfather ‘Alewi, the son of Eilsi of Faringdon’ (London, National Archives, MS E315/46 (124)).

As Stenton observed, this is a remarkable charter, for ‘there are very few cases in the whole of England in which an estate can be shown to have passed by direct descent from a man of this class to a landholder of some local consequence in the thirteenth century’ (Stenton 1939: 388; Stenton 1944: 333−34). Domesday Book records that Aluui (Alwig) held 1 hide at Milton-under-Wychwood from a certain Roger (probably Roger d’Ivry) in 1086; the pre-Conquest holder is not identified (GDB 161b (Oxfordshire 59:21)). This is clearly Alwig son of Alsige of Faringdon (Alwig 39), and it was presumably he who held the house-plot at Wallingford. He can be identified as the holder of three further properties.

(i) Bletchingdon in Oxfordshire. Domesday Book records that Alwi uicecomes (‘the sheriff’) held 2.5 hides worth 40 shillings in chief in 1086, and that a certain Manasses ‘bought this land from him without the king’s permission’; the pre-Conquest landholder is not identified (GDB 160d (Oxfordshire 58:27)). This entry occurs among the estates assigned to ‘servants of the king’ in the Oxfordshire Domesday, immediately before the entries which describe Alsige of Faringdon’s tenure of Rocote and Shipton-under-Wychwood. The estate was later held by serjeanty, for the service of providing a spit for roasting the king’s dinner when he hunted in Cornbury Forest (Maxwell-Lyte 1920–31: i, 253; ii, 1374). It is not clear when or where Alwig served as sheriff. The Bletchingdon entry is the only one in the Oxfordshire folios to name him as uicecomes, and no other text names an Oxfordshire sheriff named Alwig. The name Aluui uiceomes also occurs in the Gloucestershire Domesday (GDB 162d, 163a (Gloucestershire 1,2, 1,13)), but it is unlikely that he was identical with Alwig of Bletchingdon, for Domesday clearly implies that the Gloucestershire Aluui was King Edward’s sheriff, and he is more plausibly identified with Alwine, the pre-Conquest sheriff of Gloucestershire who died during the Conqueror’s reign (GDB 167b (Gloucestershire 34,8, 34,12); Williams 1989: 23).

(ii) Nether Worton in Oxfordshire. Alwi held in chief 2 hides less 1 virgate worth 40 shillings at Nether Worton in Oxfordshire in 1086, which had been held by a certain Leofgeat TRE. This entry also occurs among the list of estates assigned to ‘servants of the king’ in the Oxfordshire Domesday (GDB 161a (Oxfordshire 58:37)). It was also later held by serjeanty, for the service of bearing a banner before the foot of the levies of Wootton Hundred (Maxwell-Lyte 1920–31: I, 253, 589; ii, 1375−6, 1397).

(iii) Oxford. A certain Aluui held a property (mansio) in the city of Oxford in 1086 (GDB 154b (Oxfordshire B:10)). Since the son of Alsige of Faringdon is known to have held property at Wallingford in 1086, he may well have done so in Oxford as well, especially if he served as sheriff.

Estate management

To summarize the findings thus far: Alsige of Faringdon held 2 manors assessed at 7 hides and worth about £7 in 1066. One of these was the manor of Longney in Gloucestershire, where he possessed a classic thegnly residence with an adjacent church; another formed part of a large manor at Littleworth in Berkshire held by Earl Harold. It is possible that he was then Harold’s man, and that he served him by managing his estates; or that he was King Edward’s man, and served the king by managing comital manors. However this may be, by 1086, Alsige not only retained control of both of these manors, but had prospered such that he by then held 6 manors in chief, assessed at about 18 hides and worth just under £23; 2 manors as a subtenant (Littleworth and Windrush) assessed at 5.5 hides and worth just under £10; plus 3 manors (Langford, Shipton-under-Wychwood and Great Barrington) at farm form the king. The value of the latter should be excluded from the total value of his holdings, though he may well have profited from managing these manors. Even so, his holding of 23.5 hides generating a net income of about £33 placed him among the top 300 landholders in the kingdom ranked by wealth in 1086, and among the top 20 English landholders at that date. In addition, his son Alwig also prospered, for in 1086 he held an urban tenement in Wallingford and probably one in Oxford, plus manors at Nether Worton and Bletchingdon in chief, and at Milton-under-Wychwood from Roger. In total, Alwig’s estates were assessed at just over 5 hides and were attributed a value of £11 in 1086.

Alsige and Alwig clearly formed part of that select group of Englishmen who prospered within the Norman regime. In seeking to account for their success, it is surely relevant that both men possessed expertise in estate management. The clearest evidence for this is the fact that Alsige held four estates ‘at farm’ from King William, for this almost certainly meant that he was responsible for managing those estates for the king. The best analysis of what Domesday means when it says that someone held ‘at farm’ from another lord remains that of Reginald Lennard (Lennard 1959: 105−175). He shows that the valet or value assigned to each property in Domesday Book represented the amount of income it was expected to generate each year, and that those who held manors ‘at farm’ from a lord were responsible for rendering a fixed sum in cash to their lord, regardless of how much income it actually generated in any given year. This method of estate management allowed the lord to draw a stable income from an estate, and allowed the person responsible for farming it to assume its risk of profit or loss – that is, the difference between the value rendered to the lord and the actual income it generated. On this interpretation, Alsige of Faringdon would have been liable to pay the king £81 for the estates he managed on his behalf.

Three further pieces of evidence point in the same direction. First, the value of the estates held by Alsige and Alwig increased appreciably between 1066 and 1086: by 62% and 120% respectively. This was much higher than the average for the shires in which Alsige and Alwig held land: the average change in the value of comparable estates (those for which values are supplied for 1066 and 1086) in Gloucestershire, Berkshire, and Oxfordshire was -1%, 1% and 7% respectively (data from Palmer 2010). The value of the estates held by Alsige at farm increased by a relatively modest 8% in the same period, but here we should recall the possibility that the income Alsige generated from these estates could have been much higher than their aggregate ‘value’, enabling him to profit from the difference.

Second, the distribution of ploughs on the estates held by Alsige and Alwig suggest that they placed considerable emphasis on demesne agriculture: that is to say, they tended to generate income from their estates by managing them directly, extracting labour rents from dependent peasants to work the demesne and marketing their produce themselves, in preference to collecting cash rents from dependent peasants. This is reflected in the unusually high ratios of demesne to non-demesne ploughs on their estates – this ratio was 13:3 in the case of Alsige, and 3.5:1 in the case of Alwig (for comparison, the ratio for the estates which Alsige held ‘at farm’ was 15:39; and for the interest and significance of these ratios Harvey 1983).

Third, the entries for Barcote and Littleworth reveal that the fiscal assessment of these estates had been reduced between 1066 and 1086: Barcote had been reduced from 5 to 2 hides, and Littleworth had been reduced from 31 hides to zero − including, by implication, Alsige’s holding within it. It is tempting to speculate that Alsige of Faringdon was in part responsible for these reductions, which would have reduced his liability for taxation and other burdens of royal administration. Finally, the entries relating to the estates of Alsige and Alwig contain further suggestive hints of what they may well have regarded as astute estate management, but which others perhaps regarded as sharp practise. The entry for Bletchington contains the cryptic assertion that ‘Manasses bought this land from him [Alwig] without the king’s leave’; that for Littleworth records contains the possibly contradictory assertion that ‘Alsige holds 2 hides which belonged to the villans; he himself held them TRE’. The first of the two Windrush entries complains: ‘This manor which Alsige holds of the abbot unjustly lay in Salmonsbury Hundred after Bolla died; now it lies in Barrington Hundred by the judgement of the men of the same hundred’. We know that Alsige held the manor of Great Barrington at farm from the king. It is therefore probable that he was responsible for removing administratively Windrush into Barrington hundred, and that he did so to tighten his grip over this disputed estate, not least the men of Barrington hundred were much more likely to vouch him to warranty for the estate − as they appear to have done in 1086. The evidence combines to suggest that Alsige and Alwig, in common with many other agents of royal government in this period, found ways to profit from the power they exercised (Campbell 1987).

An estate with a rationale? Alsige’s economic interests

There were other ways to maximise income besides exploiting peasants and local administrative power. Indeed, there are reasons for thinking that Alsige’s unusually effective estate management involved the exploitation of four commodities − wool, salt, fish and building-stone − and the major routeways to which his distribution of properties gave him access. It is also possible that Alsige had an entrepreneurial role in the development of the place from which he took his name.

Wool. Alsige’s holdings at Great Barrington and Windrush were in prime Cotswold sheep country. It is an odd and surely not random fact that those same sheep-pastures would, a few decades later, be run from a monastic base that was next-door to Alsige’s Longney residence, namely Llanthony Priory (Elrington and Morgan 1965: 19; Hurst 2005: 65, 69). While there is no evidence for direct continuity in this nexus of exploitation between the Severn valley and the eastern Cotswolds, it illustrates that a share in the best wool-pastures would have made excellent sense as part of Alsige’s portfolio, whether viewed from Longney or from Faringdon.

Salt. The overland distribution network of that prized and essential commodity, Droitwich salt, included salt-routes through the Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire Cotswolds to transit-points on the upper Thames and in the Chilterns (see for instance the map in Blair 1994: 85). Two of these routes passed through, or very close to, Alsige’s estates: to Lechlade via Barrington and Windrush, and to Bampton via Shipton-under-Wychwood. The market customal of Faringdon includes salt-tolls, and this salt presumably reached the town either from Lechlade or by the Radcot Bridge route. Since Domesday Book lists Bampton, but not Faringdon, as having existing salt-rights in Droitwich (GDB 154c (Oxfordshire 1:6)), we may see traces here of a commercial rivalry between that ancient minster centre and Alsige’s base: a rivalry that Faringdon would win thanks to the Radcot route, leaving Bampton isolated and economically stagnant.

Fish. The main function of Droitwich salt was the preservation of foodstuffs. If Alsige had access to salt, he was also extremely well-supplied with fish. Longney was one of the main fisheries on the Severn, and fish was always an important part of its economic life (Elrington and Herbert 1972: 197−8). In the upper Thames region, Domesday Book mentions fisheries at Faringdon and Littleworth, and later lords of Radcot were concerned to protect their fishery in negotiations with their neighbours across the river (Blair 2007: 289−90). A proprietor such as Alsige could well have produced a surplus of salted river-fish, to supply for instance the growing urban populations of Oxford or Gloucester.

Taynton stone. In the later seventeenth century, under the stimulus of demand from post-fire London, fine oolitic limestone from the Taynton area in west Oxfordshire was being loaded on the Thames at Radcot and sent down-river. In the later eleventh century, Alsige may have been doing much the same. It is known that quarrying here increased sharply in response to the building-boom after 1050 (Jope 1964). Taynton itself (with its quarry mentioned in Domesday Book) was given by Edward the Confessor to Saint-Denis, but the other main quarry sites later included places that are now familiar to us: Barrington, Windrush and Milton-under-Wychwood. If quarrying was indeed one of Alsige’s enterprises, his control of Radcot put him in an especially good position to supply clients in the middle and lower Thames valley.

Travel by water and road. From the point of view of water-transport, Alsige’s main residences were in two of the best locations in England: Longney just above Framilode at the start of the Severn estuary, Faringdon/Radcot at a major break-point on the Thames that may have been the head of navigation for large-scale freight (Blair 2007: Blair, pp. 17−18, 121, 282−3). Whatever surpluses he may have been marketing − wool, salt, fish, stone, and very likely grain − he was perfectly placed to send them to the important and expanding local centres of Oxford and Gloucester, as well as the international entrepots of London and Bristol. To bring into consideration the Buckinghamshire Alsige is to draw attention to a major route of a different kind, the over-land one that led from the west midlands to London via the Chilterns. This is shown to us most vividly in the stories of miracles performed by Saint Wulfstan of Worcester as he stopped overnight at High Wycombe on the way to London (Winterbottom and Thomson 2002: 76−81). Like Wulfstan and other public figures, Alsige would have led an active and mobile life: looking after his own interests and the king’s, combining business at Faringdon with pleasure at Longney, perhaps fulfilling duties at court. Despite the commercial advantages of the river, his own route to London would have been by road: it is implausible to imagine a rich man negotiating the upper Thames in a punt, bumping over shallows and shooting flash-locks like his own merchandise. For regular journeys through the Chilterns, Chesham would have been as convenient a base for Alsige as Wycombe was for Wulfstan.

The town of Faringdon. The Domesday entry for Faringdon hints at the incipient market town in its reference to ‘nine house-plots (hagae) in the vill’ which generated an income of 40 shillings (GDB 57d (Berkshire 1:34)). Deeds and customals in the Beaulieu Abbey cartularies show that the number of burgages was still expanding in the early thirteenth century, and describe market rights and tolls (London, British Library, MS Cotton Nero A xii; Bodleian Library, MS Barlow 49). Although Domesday does not link this urbanisation to Alsige, it seems likely that he had some formal role (perhaps as port-reeve?) in the place by which he was generally known. The location of the town, at the point where the road from Radcot Bridge joins the old Lechlade to Wantage road, suggests that Faringdon’s commercial success may have been intimately connected with the development of Radcot and its causewayed Thames crossing. As discussed below, some Faringdon tenements were held by a distinct ‘tenura de Alsy’ as late as the thirteenth century.

It is rarely easy to ascribe economic motivation and strategies to early medieval people. Nonetheless, the facts as we have them are compatible with the hypothesis that Alsige was not only an important administrator under William the Conqueror, but also a significant entrepreneur. Even if the royal farms gave him formidable obligations to meet, the diversity of his potential sources of revenue would surely have helped him, with assiduous management, to keep well in the clear. Well might he build a lavish church at Langford, and feast lavishly under his nut-tree on a summer day.

Langford church: architectural patronage

The existing parish church at Langford constitutes vivid and unambiguous evidence of Alsige’s pretensions as a local magnate and patron. Langford had probably been a comital manor under King Edward, and retains impressive Crucifixion sculptures that may date from that time (Baxter and Blair 2006: 30−2, 39−41; Blair 1994: 135−6, 178, 180). The exceptionally lavish central tower, with its main arches and belfry openings framed in bold, tubular roll-mouldings, is clearly post-Conquest, but it perpetuates Anglo-Saxon details in its pilaster strips, double-splayed windows, and the foliage decoration on the capitals of the belfry openings (Taylor and Taylor 1965: i, 367−72; D. Tweddle et al. 1995: 213−15).

The tower of Langford church, Oxfordshire (photograph by John Blair)

Built into the south wall of the tower is carved sundial, supported on the upstretched arms of two wiry figures who are strongly reminiscent of the Bayeux Tapestry.

The sundial of Langford church, Oxfordshire (photograph by John Blair)

This is a classic ‘overlap’ building: the fusion of traditions shows an interest in embracing the English as well as the Norman cultural heritage, and given that in 1086 the king was farming Langford to Alsige, it seems overwhelmingly likely that he, not William I, commissioned it. A close (though still grander) analogy is the magnificent ‘overlap’ church at Milborne Port (Somerset), and it cannot be coincidence that this belonged in 1086 to that other hardy survivor, the ex-chancellor Regenbald (Keynes 1988). Here we can see the architectural aesthetic of the small but influential band of survivors from Edward’s administration, Alsige included, who secured roles for themselves in William’s. We know from the nut-tree story that Alsige was interested in church-building. He may have chosen Langford because Faringdon church, a probably ex-minster now in the hands of Salisbury cathedral, was outside his control, though given his background and local status, the probable association of Langford church with the now-departed earls of Wessex and Mercia must have made it an attractive object for his patronage.

Radcot: the river-crossing and the castle

The small and seemingly insignificant estate at Radcot, held by Alsige in 1086 and perhaps earlier by Harold, was in fact of great importance in regional communications and military strategy. Before the building of Newbridge in the late middle ages, and Swinford bridge in the eighteenth century, it was the next major crossing up-river from Oxford. Its strategic importance is underlined by the sequence of sieges and engagements that occurred there: between Stephen and Matilda in 1142; between the forces of Richard II and the Lords Appellant in 1387; between royalist and parliamentary troops in 1644−5; and the prospective but unrealised conflict represented by a pill-box from 1940. It would also have been the main link between Alsige’s cluster of estates around Faringdon, south of the river, and Langford and Shipton to its north. The road which links Burford and other Oxfordshire places to Faringdon crosses the Thames at Radcot bridge. It is notably straight and artificial, and is partly causewayed: it is tempting to suspect some affinity with Robert d’Oilly’s great causeway at Grandpont in Oxford (Dodd 2003), and to wonder whether Robert’s contemporary, Alsige of Faringdon, could have had something to do with its construction.

These possibilities have been strengthened and extended thanks to a geophysical survey by Roger Ainslie of Abingdon Archaeological Geophysics, followed by a three-day excavation by Channel 4’s Time Team in 2008. The results of this are still provisional, pending full analysis of the pottery, but they are exciting. After a long interlude since the late Roman period, occupation on the north bank of the Radcot crossing seems to have recommenced around the mid eleventh century. Soon after this, a massive stone keep was built beside the apparent original line of the causeway over the Thames.

Excavations of Radcot keep (photograph courtesy of John Blair)

In the mid to late twelfth century (probably though not certainly after the documented siege by King Stephen in 1142), a courtyard house with domestic ranges and a chapel was attached to the tower on its south-east side, and the road diverted around the perimeter of a curtain wall and moat. This was presumably done by the de Bucklands (see below), whose heirs occupied the house into the fourteenth century, but the pottery evidence suggests that the keep had been demolished by 1200.

At present it is unclear, and may remain unclear, whether the keep was built before or after 1086, but there is nothing inherently unlikely about a very early Norman date. In fact, it has recently been realised that St George’s tower at Oxford Castle − smaller but very similar in plan − slightly pre-dates the Conquest. An eleventh-century stone keep in such a rural location, well away from any significant settlement, is most unusual: its purpose must have been strategic, to command this crucial river-crossing, and the broad basin between the Cotswolds to the north-west and the Corallian Ridge and Vale of the While Horse to the south. Was it then built under William I’s directions, as a defensive and pacificatory measure? And was its castellan the English collaborator Alsige of Faringdon, just as the parvenu Robert d’Oilly (who like Alsige had married the heiress of an English magnate) was castellan at the next major crossing down-river?

The descent of Alsige’s holdings

Alsige was dynastically successful to the extent of founding a line of Oxfordshire gentry, the de Astrops. This, however, was through his son Alwig, who by 1086 was already holding the hide at Milton-under-Wychwood in his own name as Roger d’Ivry’s tenant, and whose descendants based themselves at Astrop in Brize Norton, also on Roger d’Ivry’s fee (Pebberdy 2006: 222). Alsige’s own federation of estates was at least partly dismembered on his death, reverting in part or whole to the Crown. They may be considered in three main groups.

Faringdon and its members. The great manor of Faringdon, with detached members, was in royal hands through most or all of the twelfth century, and given by King John to Beaulieu Abbey (Garbett 1924: 492; Dugdale 1846: v, 683). Outliers at Great Barrington, Inglesham, Langford, Little Faringdon and Shilton, which were topographically in Gloucestershire, Wiltshire and Oxfordshire, remained members not only of the manor but also of Faringdon hundred, and thus administratively in Berkshire (Round 1906: 319; Thorn 1988: 31). This complex pattern remains to be analysed; the distribution of outliers corresponds closely to that of Alsige’s former holdings, but whether the detached fragments of Faringdon hundred represent his holdings, or royal estates from which they were formed, is currently undefined. Intriguingly, the distinctness of Alsige’s holding in Faringdon was still remembered in the thirteenth century, when it was stated that ‘tres sunt tenure in predict villa, scilicet tenura regis, tenura episcopi [i.e. of Salisbury], et tenura de Alsy’ (‘there are three tenures in the aforesaid vill, namely the king’s tenure, the bishop’s tenure, and the tenure of Alsige’: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Barlow 49, fo. 109v).

The ‘de Buckland’ fee. At various points from 1141 onwards, holdings that had been Alsige’s in 1086 are recorded in the hands of the de Bucklands or, after c. 1176, their heiresses. This was an important north Berkshire family who took their name from Buckland, immediately east of Faringdon, and whose founder was Hugh de Buckland, one of the ‘new men’ whom I King Henry raised ‘from the dust’, and his main official in north Berkshire (Bradley and Hudson 2004; Keats-Rohan 2002: 330; Green 1986: 237). The pipe roll of Henry I reveals that Hugh’s son William held Faringdon in Berkshire at farm in 1130 (Hunter 1833: 127), and a charter issued by the Empress Matilda in 1141 reveals that William also held Great Barringon in Gloucestershire in at farm prior to that date (Cronne and Davis 1968: no. 497). This suggests a degree of continuity in tenurial arrangements, for Alsige had both of these estates at farm in 1086. In addition, the Buckland family can be shown to have held Barcote by c. 1180 (Historical MSS Commission Rep. xiii, App. iv, 379, citing a now-lost deed); Windrush by 1198 (Elrington and Morgan 1965: 180); Littleworth (or the 4 hides in Faringdon (?)) by c. 1200 (Garbett 1924: 493); and Radcot by 1220 (Hockey 1974: 16−18). It is highly implausible, even if theoretically possible, that the family acquired these properties piecemeal, and the natural conclusion is that a large section of Alsige’s former estate was transferred en bloc to the Bucklands at some date before 1130. We know nothing of Hugh of Buckland’s origins: he could well have received the group of manors from Henry I as a going concern, but it is also conceivable that he inherited them from Alsige by descent or marriage. At any rate his role in the upper Thames region under Henry I may not have been dissimilar from Alsige’s role there under Henry’s father; it seems very likely that he was in control of, and possibly built, the keep at the Radcot crossing.

Longney. In the early twelfth century the manor was given to Malvern Priory by Osbern fitz Pons, who had received it, according to Henry I’s confirmation, by gift of William I (Dugdale 1846: iii, 448). If this is a reliable statement, it means that Longney must have reverted to the Crown in time to be granted out again before the Conqueror’s death in September 1087, which in turn means that Alsige must have died (or, conceivably, have forfeited his lands) within a few months of the Domesday inquest. But the charter is spurious.

Bibliography

Baxter and Blair 2006: S. Baxter and J. Blair, ‘Land Tenure and Royal Patronage in the Early English Kingdom: a Model and a Case Study’, Anglo-Norman Studies 28 (2006), 19−46

Blair 1994: J. Blair, Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire (Stroud, 1994)

Blair 2007: Waterways and Canal-building in Medieval England, ed. J. Blair (Oxford, 2007)

Bradley and Hudson 2004: H. Bradley, ‘Buckland , Hugh of (d. 1116x19)’, rev. J. Hudson, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004)

J. Campbell, ‘Some Agents and Agencies of the Late Anglo-Saxon State’, in Domesday Studies, ed. J. C. Holt (Woodbridge, 1987), pp. 201–218; repr. in his The Anglo-Saxon State (London, 2000), pp. 201–27

Clarke 1977: H. B. Clarke, ‘The Early Surveys of Evesham Abbey: an Investigation into the Problem of Continuity in Anglo-Norman England’, unpublished Ph.D. thesis (University of Birmingham, 1977)

Cronne and Davis 1968: Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum 1066−1154, Volume III, ed. H. A. Cronne and R. H. C. Davis (Oxford, 1968)

Dodd 2003: A. Dodd, Oxford before the University: The Late Saxon and Norman Archaeology of the Thames Crossing, the Defences and the Town (Oxford, 2003)

Dugdale 1846: W. Dugdale, Monasticon Anglicanum, ed. J. Caley, H. Ellis, and B. Bandinel, 6 vols in 8 (London, 1846)

Elrington and Herbert 1972: C. R. Elrington and N. M. Herbert, ‘Whitstone Hundred’, The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Gloucestershire, Volume X, ed. C. R. Elrington and N. M. Herbert (London, 1972), pp. 119–299

Elrington and Morgan 1965: C. R. Elrington and K. Morgan, ‘Slaughter Hundred’, The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Gloucestershire, Volume VI, ed. R. B. Pugh (London, 1965), pp. 1–184

Garbett 1924: L. E. Garbett, ‘Hundred of Faringdon’, The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Berkshire, Volume IV, ed. W. Page and P. H. Ditchfield (London, 1924), pp. 486–99

Green 1986: J. A. Green, The Government of England under Henry I (Cambridge, 1986)

Harvey 1983: S. P. J. Harvey, ‘The Extent and Profitability of Demesne Agriculture in the Later Eleventh Century’, in Social Relations and Ideas: Essays in Honour of Rodney Hilton, ed. T. H. Aston et al. (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 4573

Hockey 1974: The Beaulieu Cartulary, ed. S. F. Hockey (Southampton, 1974)

Hudson 2002–7: Historia Ecclesie Abbendonensis: The History of the Church of Abingdon, ed. and trans. J. Hudson, 2 vols, (Oxford, 2002–7).

Hunter 1833: Pipe Roll 31 Henry I, ed. J. Hunter, Record Commission (London, 1833)

Hurst 2005: D. Hurst, Sheep in the Cotswolds: The Medieval Wool Trade (Stroud, 2005)

Jope 1964: E. M. Jope in Medieval Archaeology 8 (1964), 91−118

Lennard 1959: R. Lennard, Rural England 1086–1135: A Study of Social and Agrarian Conditions (Oxford, 1959)

Keats-Rohan 2002: K. S. B. Keats-Rohan, Domesday Descendants: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents 1066–1166, II, Pipe Rolls to Cartae Baronum (Woodbridge, 2002)

Keynes 1988: S. Keynes, ‘Regenbald the Chancellor (sic)’, Anglo-Norman Studies 10 (1988), 185–222

Maxwell-Lyte 1920–31: Liber Feodorum or The Book of Fees commonly called Testa de Nevill, ed. H. C. Maxwell-Lyte, 3 vols (London, 1920–31)

Moore 1082: Domesday Book 15: Gloucestershire, ed. and trans. J. S. Moore (Chichester, 1982)

Palmer 2010: J. Palmer, Electronic Edition of Domesday Book: Translation, Databases and Scholarly Commentary, 1086 (2nd Edition, 2010), UK Data Service. SN: 5694, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5694-1

Pebberdy 2006: R. B. Pebberdy, ‘Brize Norton’, The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Oxfordshire, Volume XV, ed. S. Townley (London, 2006), pp. 205–46

Round 1906: J. H. Round, ‘Domesday Survey’, The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Berkshire, Volume I, ed. W. Page (London, 1906), pp. 285–321

Stenton 1939: F. M. Stenton, ‘Domesday Survey’, The Victoria History of the Counties of England: A History of Oxfordshirre, Volume I, ed. L. F. Salzman (London, 1939), pp. 373–95

Stenton 1944: F. M. Stenton, ‘English Families and the Norman Conquest’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 4th series 26 (1944); repr. in and cited from his Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England: The Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton, ed. D. M. Stenton (Oxford, 1970), pp. 325–34.

Stone and Hyde 1968: Oxfordshire Hundred Rolls of 1279, ed. and trans. E. Stone and P. Hyde, Oxfordshire Record Society 46 (1968)

Taylor and Taylor 1965: H. M. Taylor and J. Taylor, Anglo-Saxon Architecture, 2 vols (Cambridge, 1965)

Thorn 1988: F. R. Thorn, ‘Hundred and Wapentakes’, in The Berkshire Domesday, ed. A. Williams and R. W. H. Erskine (London, 1988), pp. 29−33

Tweddle et al. 1995: D. Tweddle et al., Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Sculpture IV: South-East England (Oxford, 1995)

Von Feilitzen 1937: O. Von Feilitzen, The Pre-Conquest Personal Names of Domesday Book (Uppsala, 1937)

Williams 1989: A. Williams, ‘An Introduction to the Gloucestershire Domesday’, in The Gloucestershire Domesday, ed. A. Williams and R. W. H. Erskine (London, 1989), pp. 1–39

Williams 1991: A. Williams, The English and the Norman Conquest (Woodbridge, 1991)

Williams 1992: A. Williams, ‘A Bell-house and a Burh-geat: Lordly Residences in England before the Norman Conquest’, Medieval Knighthood 4 (1992), 221–240

Williams 2008: A. Williams, The World before Domesday: The English Aristocracy, 900−1066 (London, 2008), pp. 85−104

Winterbottom and Thompson 2002: William of Malmesbury, Vita Wulfstani, ed. and trans. M. Winterbottom and R. M. Thompson in William of Malmesbury: Saints’ Lives (Oxford, 2002), pp. 7–156.